Essential Care and Maintenance

Natural Stones

Do’s & Dont’s – Routine Preventive Measures

- Use coasters under drinking glasses — particularly those containing alcohol or citrus juices — to avoid etching.

- Place hot items directionly on the stone surface. Use trivets or mats under hot dishes.

- Use place mats under china, silver or other objects that can scratch the surface.

- Avoid cleaning products unless the label specifies it is safe for natural stone. This includes glass cleaners to clean mirrors over a marble vanity top, or a liquid toilet bowl cleaner when the toilet is on a marble floor.

Do’s & Dont’s – Treating Spills

Some spills will turn out to be detrimental to stone if unattended. Orange juice, lemonade, wine, vinegar, liquors, tomato sauce, yogurt, salad dressing, perfume, after shave, the wrong cleaning products and so on — through a long list — most likely won’t damage “granite” and “green marble” (at least in the short run), but will etch marble, travertine, limestone, onyx, alabaster and many slates. Therefore:

- Pick up any spills as quickly as possible.

- Rub the spill; only blot it.

- Use cleaning products on or near your natural stone unless the label specifies that it is safe on natural marble. (Cultured marble is man-made and basically a plastic material.) This includes glass cleaner to clean the mirror over a marble vanity top, or a liquid toilet bowl cleaner when the toilet is on a marble floor.

Floors

Invest in Quality Cleaning Tools

A cleaning chore — any cleaning chore — is never a matter of cleaning product only. The implements (cleaning rag, paper towel, scrubbing pad, squeegee, etc.) are important considerations as well. A good quality mop and the proper mopping bucket are critical to obtaining the best results when mopping your highly polished stone or porcelain floor.

We found that sponge mops are not the best choice for highly polished stone floors. A better choice is a good-sized, closed-loop cotton string mop. However, the very best are micro-fiber mops.

Always make certain that buckets, brushes, mops, rags, etc., are free from any grit or residues that might scratch or otherwise mar the floor’s surface. It is also advisable to use only white or colorfast cloths. You don’t want any dyes in colored cloths or sponges to be left behind on your floor.

A Note on Newly Installed Floors

The best thing to have done to a brand-new polished stone floor is a detailing job by a properly trained maintenance contractor, or a professional stone restorer/refinisher. Detailing means deep-cleaning the entire floor thoroughly, removing all possible grout residue or film and adhesive, and perhaps addressing minor factory flaws or possible small damages left behind by installers. (See Initial Cleaning if Newly Installed Tile Floor.)

Equipment Check

Always make certain that buckets, brushes, mops, rags, etc. are free from any grit or residues that may remain from previous use, which can mar the marble you are cleaning. Be careful to use only white or colorfast clothes, because the dyes in colored clothes or sponges may discolor lighter marbles.

Kitchen Counter Tops

Assuming that your kitchen counter top is made either out of true granite, green marble or soapstone, or a hone-finished stone (if you have polished marble or polished travertine, then there’s not much that can be done to maintain their highly glossy finish, other than…well, never using your counter top), there is one thing you must remember:

This firm rule applies to all stone surfaces — counter tops, floors, walls, etc. — using a “glass cleaner” or “water with a little dish soap” are common but erroneous recommendations that you may hear. Glass cleaners may turn out to be too harsh to both the stone and the sealer (if one has been applied). Water and dish soap can leave an unsanitary and unsightly film that will build up and become problematic to remove. (Wash your hands with dish soap and then rinse them under running water; observe how long and how much water it will take to rinse properly. To get the same rinsing result — which is the only one acceptable— for your counter tops, you would have to rinse them with a garden hose!)

Generic household cleaners off the shelves of the supermarket are out, and specialty cleaners specifically formulated to deal with the delicate chemistry of stone are, very definitely, in order.

Dos & Don’ts – Kitchen Counter Tops

- Clean your kitchen counter top regularly with an appropriate stone-safe cleaner. Use a hgher concentration near cooking and eatin areas, and diluted water for less demanding situations such as vanity tops — areas of the counter top far from cooking and eating areas.

- Let any spills sit too long on the surface of your counter top. Clean spills up (by blotting only) as soon as you can. But, if you do have dried-on spills…

- Use any green or brown scouring pads for dried-on spills. The presence of silicon carbide grits in them will scratch even the toughest granite. You can safely us the sponges lined with a silvery net, or other plastic scouring pads. REMEMBER: it’s very important to spray the cleaner and let it sit for a while to moisten and soften the soil, before scrubbing, LET THE CLEANING AGENT DO THE WORK! It will make your job much easier and will be more effective.

- Treat your counter tops to a conditioning stone polish occasionally. It can do a terrific job at brightening up your polished stone surface. Be sure hat the ingredients are classified as “food-grade.” As with all the products, be sure to follow the label instructions.

Dos & Don’ts – Vanity Tops

- Clean your vanity tops regularly with a stone-safe, soap-free neutral cleaner appropriate for your natural stone type.

- Take chances with cleaning your mirrors over your marble vanity tops with a regular glass cleaner.

- Clean your mirror with a neutral cleaner. Even if you over-spray it, nothing bad is going to happen to your marble. TIP: Rubbing alcohol works wonders for cleaning mirrors and won’t harm marble.

- Use any powder cleanser, or — worse yet — any cream cleaner.

- Do your nails on your marble vanity top, or color or perm your hair near it.

- Place any wet bottle on it (perfume, after shave, etc.). Keep your cosmetics and fragrances in one of those pretty mirror trays (be sure that the legs of the tray have felt tips) or other appropriate container.

- Use a stone polish if you want to add extra shine to your polished stone counter top surface and help prevent soiling.

Dos & Don’ts – Shower Stalls

- Monitor your grout and chaulk lines periodically and address any problem immediately.

- Use any cleanser, either in a powdery or creamy form.

- Use any mildew stain remover, such as TILEX MILDEW STAIN REMOVER or X-14 MILDEW STAIN REMOVER on your polished stone shower stall.

- Use any mildew stain remover, such as TILEX MILDEW STAIN REMOVER or X-14 MILDEW STAIN REMOVER on your polished stone shower stall.

- Use any self-cleaners, such as SCRUBFREE and the like, or any harsh disinfectant, such as LYSOL.

- Clean your shower stall daily. The easiest and most effective way is to spray the walls and floor of the stall with an appropriate cleaner, then squeegee, after everybody in the home has taken a shower for the day.

- Use a soap film remover specifically formulated to be effective at doing the job of cleaning soap scum and hard mineral deposits, while not negatively interacting with the chemistry of natural stone.

- Clean mildew stains that appear on the grout lines of your shower enclosure with a mildew stain remover that has been formulated to be safe on natural stone, while being very effective at removing mildew and other biological stains.

Dos & Don’ts – Toilets

- Use any regular toilet bowl cleaners if your toilet is places on a marble or other natural stone floor. They are highly acidic. Possible spills will dig holes in your marble. Clean your bowl with a non-acidic toilet bowl cleaner.

Sealing and Protecting

All stone is porous, some more than others. For most stone – especially very porous stones like hone-finished limestone or certain granites – the application of a quality impregnating sealer is highly recommended.

The application of an impregnating sealer to highly-polished marble and travertine, or polished high-density granites, may not be necessary – but when in doubt, consider this: it doesn’t hurt to have it sealed. If it turns out that sealing the stone does, in fact, prevent some staining, you’ve saved yourself the cost of a stain removal service.

How many applications of sealer are needed?

For some stones that are more porous than others, one application of impregnator/sealer may not be enough. But how will you know?

On granites that need sealing, at least two applications are recommended. Very porous granites, sandstone, quartzite, etc., may require three or more applications. When sealer can no longer be absorbed by the stone, the stone is adequately sealed.

How long will it last?

There is no absolute rule of thumb when it comes to the durability of any sealer. Generally speaking, most quality impregnating sealers interior will last 2-5 years or more. Environment plays a big role. Stones exposed to intense heat or direct sunlight will probably need to be re-sealed more often.

When is it time to reseal?

To find out if your stone is perfectly sealed, pour some water on it and wait for approximately half an hour, then wipe it dry. If the surface of the stone did not darken, it means that the stone is still perfectly sealed. Be sure to test various areas, especially those areas that get more use and abuse.

What does a sealer do?

Contrary to what your perception may be when you hear the word sealer, most sealers for stone are below-surface products and will not alter in any way, shape, or form the original finish produced by the factory. They will not offer protection to the surface of the stone, either. They will only go inside the stone by being absorbed by it (assuming that the stone is porous enough to allow this to happen) and will clog its pores, thus reducing its natural absorbency rate. This will help prevent possible accidental spills of staining agents from being absorbed by the stone. On the other hand, granite is more porous than marble and may stain if not protected with a good-quality, impregnator-type stone sealer. Stay away from topical sealer, waxes, and coatings. Some “granites” are so porous that no sealer will do a satisfactory job sealing them 100% for an extended amount of time.

Sealers for stones, which are below-surface, penetrating-type sealers – better referred to as impregnators – are designed to do one thing and one thing only: clog the pores of the stone to inhibit staining agents from being absorbed by it. In some instances, “weird” problems that may appear to be etching on “granite” counter tops turn out to be created by sealer residue that has left a haze on the stone or reacted with substances that had spilled on it. In these cases, once the sealer is professionally removed, everything is fine.

Note: Sometimes, marks of corrosion (etch marks) that an acidic substance leaves behind may look like water stains or rings, but they are neither stains, nor were they generated by water. The deriving (surface) damage has no relation whatsoever with the porosity of the stone (which determines its absorbency), but is exclusively related to its chemical makeup. Special topical treatments are becoming available for acid-sensitive stones that are designed to offer some protection from acids, while still allowing the stone to breathe. Ask us for more information on this

Color Enhancing Sealing

While impregnating sealers will not alter the appearance of your stone, a color-enhancing (impregnating) sealer will protect the stone while bringing out its color, giving it a wet (i.e. darker, not glossy) look. It will at the same time provide good protection from water-based staining. Color enhancing sealers are typically used on tumbled marble, low-honed limestone and travertine, hone (black) granite, etc.

Sealing: DIY or Call In a Pro?

Is sealing a job for the homeowner, or should you hire a qualified professional to do it for you? Consider the following pros and cons.

You save on labor costs by doing it yourself. However, consider the magnitude of the job and how comfortable you are with a DIY project. Are you prepared to get on your hands and knees to seal a floor? Are you willing to apply multiple applications if needed?

Different sealers perform differently in different environments and on different stones. Hiring a pro to do the job may end up saving you in the end. A pro will know which is the best sealer for the job and will use equipment and techniques that allow them to get the job done efficiently.

Sealing Grout – Clear or Color Sealing?

Cementitious grout is porous and will absorb liquids which can potentially stain and result in the growth of bacteria. Sealing your grout provides a protective barrier that not only preserves it from stains, it makes routine cleaning and maintenance easier.

Grout can be sealed with a clear sealer or it can be color sealed. Color sealing has the added advantage that it allows you to completely change the color of your grout, whether it is just for a new look or to cover up stained and discolored grout.

Stain Management

Stains come from many sources, but most are removable.

The key to success is cleaning up any spills and treating any resulting stains as soon as you can. Understanding the source of the stain will help in determining the best treatment. Many options are available for treating stains on natural stone from creating your own poultice to using convenient ready-made poultices. Ask us for help if you need it.

All stones are, more or less, absorbent. One may say that diamonds or gemstones are not absorbent. That’s right, but a gemstone is not actually a stone. It is actually made of one crystal of one single mineral.

All other (less noble) stones are the composition of many crystals, either of the same mineral, or of different minerals bonded together, The “space” in between these molecules of minerals is mostly what determines the porosity of a stone. The porosity of stone varies greatly, and so does, of course, their absorbency. Some of them are extremely dense, therefore their porosity is minimal. What this translates into is the fact that the absorbency of such types of stone is so marginal that – by all practical intents and purposes – it can be considered irrelevant. Some other stones present a medium porosity, and others at the very end of the spectrum are extremely porous. Because of their inherent porosity, many stones will absorb liquids, and if such liquids are staining agents a true stain will occur.

Is it really a stain?

A true stain is always darker than the stained material. If it appears as a lighter color it is not a stain, but either a mark of corrosion (etching) made by an acid, or a caustic mark (bleaching) made by a strong base (alkali). In other words, a lighter color “stain” is always surface damage and has no relation whatsoever with the absorbency rate of the damaged material – stone or otherwise. There is not a single exception to this rule.

A stain is a discoloration of the stone produced by a staining agent that was actually absorbed by the stone. Other “discolorations” have nothing to do with the porosity (absorbency) of the stone, but rather are a result of damage to the stone surface. All those “stains” that look like “water spots” or “water rings” are actually marks of corrosion (etches) created by some chemically active liquids (mostly – but not necessarily limited to – acids), which had a chance to come in contact with the stone. All calcite-based stones such as marble, limestone, onyx, travertine, etc., are sensitive to acids. Therefore, they will etch readily (within a few seconds). Many slates will also etch and so will a few “granites” (those that instead of being 100% silicate rock are mixed with a certain percentage of caicite). Now let’s discuss how to remove stains!

How to Remove a Stain – Poulticing Method

Definition of a poultice

What’s a poultice? It is the combination of a very absorbent medium (it must be more absorbent than the stone) mixed with a chemical, which is to be selected in accordance with the type of stain to be removed. The concept is to re-absorb the stain out of the stone. The chemical will attack the stain inside the stone, and the absorbent agent will pull them both out together. The absorbent agent can be the same all the time, regardless of the nature of the stain to be removed, but the chemical will be different – in accordance with the nature of the staining agent – since it will have to interact with it. The absorbent part of a poultice could be (in order of preference): talcum powder (baby powder), paper towel or diatomaceous earth (the white stuff inside your swimming pool filter) for larger projects. NOTE: There are convenient poulticing kits that make the task of stain removal easier. You may want to ask us for some specific recommendations.

As we said before, the chemical must be selected in accordance with the nature of the staining agent.

There are five major classifications of stains:

- Organic stains (i.e. coffee, tea, coloring agents of dark sodas and other drinks, gravy, mustard, etc.)

- Inorganic stains (i.e. ink, color dies, dirt – water spilling over from flower or plant pots, etc.)

- Oily stains (i.e. any type of vegetable oil, certain mineral oils – motor oil, butter, margarine, melted animal fat, etc.)

- Biological stains (i.e. mildew, mold, etc.)

- Metal stains (i.e. rust, copper, etc.)

The chemical of choice for both organic and inorganic stains is hydrogen peroxide (30/40 volumes, the clear type – available at your local beauty salon. The one from the drugstore is too weak, at 3.5 volume).

Sometimes, in the case of ink stains, denatured alcohol (or rubbing alcohol) may turn out to be more effective.

For oily stains, our favorite is acetone, which is available at any hardware or paint store. (Forget your nail polish remover. Some of them contain other chemicals, and others contain no acetone whatsoever.)

For biological stains, one can try using regular household bleach or a mildew stain remover designated safe for stone.

For metal/rust stains, our favorite is a white powder (to be dissolved in water) called Iron-out, which can be found in any hardware store. There is also a product called RSR-2000 from Alpha Tools that is used and recommended be restoration contractors.

Etching, A.K.A. “Water Stains” or “Rings”

Polished marble, travertine, onyx, limestone, etc, are all calcite-based stones, and as such are affected by pH active liquids, mostly acidic in nature. In Iayman’s language, when an acidic liquid gets on a polished marble, travertine, slate, etc. surface, it etches it on contact. That is, it leaves a mark of corrosion that looks like a water stain or ring. Such surface damage has nothing to do with the absorbency rate of the stone (typically quite low, anyway) but exclusively with its chemical makeup, which – as mentioned before – is mostly calcite (Calcium Carbonate, CaCo3). Trying to remove that “stain” by poulticing it would be a useless exercise, since it is not a stain – no matter what it looks like.

So, how do you remove a chemical etch-mark, which as seen, is not a stain but surface damage? You don’t! In fact, an etch mark can be effectively compared to – and defined as – a shallow chemical scratch. A scratch is something missing (a groove), and nobody can remove something that is already missing. It would be like trying to remove a hole from a doughnut! The only thing one can do is eat the doughnut, – and the whole is gone! The same thing goes for a scratch you must actually remove whatever is around the groove, down to the depth of the deepest point of the scratch.

You are actually a full-fledged – though small in size – stone restoration project! Is this a task for the average homeowner? The answer is maybe. If it is polished marble, travertine, or onyx, then there’s hope. If it is hone-finished marble or travertine, or hone-finished slate (like a chalkboard), or mixed “granite”, then you probably should hire a professional stone finisher. If it’s a cleft-finished slate (rippled on its surface), then nobody can actually do anything about it, other than attempt to mask it by applying a good-quality stone color enhancer.

While marble and other calcite-based stones are vulnerable to acids, granite is much more resistant. In fact, the only acid that will etch polished granite is hydrofluoric acid, commonly found in rust removers.

If the etch is light (the depth is undetectable by the naked eye and it looks and feels smooth), then a polishing compound for marble will work quite well – without requiring the experience of a professional. In this case, no specific tools are needed other than a piece of terry cloth.

How to prepare a poultice and use it to remove stains

WEAR RUBBER GLOVES AT ALL TIMES WHILE HANDLING CHEMICALS!

If you’ve chosen talcum powder (baby powder) or other powders as your absorbent medium:

- Mix it – using a metal spatula or spoon – in a glass or stainless steel bowl, together with the chemical, to form a paste just a tad thinner than peanut butter (thin enough, but not runny). If you are attempting to remove a metal (rust) stain, first dissolve the Iron-out with water – according to the directions on the container – then mix it with an equal amount of talcum powder, adding water if it turns out to be too thick, or talcum if it is too runny.

- Apply the poultice onto the stain, going approximately ½” over it all around, keeping it as thick as possible (at least ¼”).

- Cover the poultice with plastic wrap, tape it down using masking tape, and poke a few holes in the plastic.

- Leave the whole thing alone for at least 24 hours, then remove the plastic wrap.

- Allow the poultice to dry thoroughly! It may take from a couple of hours to a couple of days or better, depending on the chemical. Do NOT peek! This is the phase during which the absorbing agent is re-absorbing the chemical that was forced into the stone, together (hopefully) with the staining agent, and you do NOT want to interrupt that process.

- Once the poultice is completely dry, scrape it off the surface of the stone with a plastic spatula, clean the area with a little squirt of natural cleaner, then wipe it dry with a clean rag or a sheet of paper towel.

- If the stain is gone, your mission is over! If some of it is still there, repeat the whole procedure (especially in the case of oily stains, it may take up to 4 or 5 attempts). If it didn’t move at all, either you made a mistake while evaluating the nature of the stain (and consequently used the wrong chemical), or the stain is too old and will not come out, or it was not a stain, but another type of discoloration.

If you decide to use a paper towel instead of talcum powder, make a “pillow” with it (8 or 10 folds thick) a little wider than the stain, soak it with the chemical to a point that’s wet through, but not dripping, apply it on the stain and tap it with your gloved fingertips to ensure full contact with the surface of the stone. Then take it from step 3 above.

Combination “Stains”

Finally, we may have a combination of a stain with etching. For example, if some red wine is spilled on an absorbent polished limestone, then the acidity of the wine (acetic acid) will etch (corrode) the surface on contact, while the dark color of the wine will stain the stone by being absorbed by it. In such a case, first you remove the stain by poulticing (hydrogen peroxide), and then repair the etching by refinishing the surface.

Ten Potential Stone Problems – And What To Do About Them

The loss of the high polish on certain marble and granite can be attributed to wear. This is especially true of marble, since it is much softer than granite. When shoes track in dirt and sand, the bottoms of the shoes can act like sandpaper on a stone floor surface and over time will wear the polish off. A stone restoration professional can restore the polish using a number of different techniques.

The dull, whitish spot created when liquids containing acids are spilled on marble is called etching. Marble and limestone etch very easily. Granite is very acid-resistant and will rarely etch. To prevent etching, avoid using cleaners and chemicals that contain acids. Light etching can be removed with a little effort and good marble polishing compound. Deep etching or large areas will require the services or a restoration professional.

Some stone surfaces can become stained easily if they are not properly sealed. Many foods, drinks, ink, oil and rust can cause stains. Most stains on stone can be removed. For some more difficult stains, professional techniques by a stone restoration provider may be the only hope. Permanent stains can occur.

Effloresence appears as a white powdery residue on the surface of a stone. It is a common condition on new stone installations or when the stone is exposed to a large quantity of water, such as flooding. This powder is a mineral salt from the setting bed. To remove efflorescence do not use water. Buff the stone with a clean polishing pad or #0000 steel wool pad. The stone will continue to effloresence until it is completely dry. This drying process can take several days to as long as one year. Do not seal the stone until all effloresence is gone.

If your stone is developing small pits or small pieces of stone are popping off the surface (spalling), then you have a problem. This condition is common on stone exposed to large amounts of water or when de-icing salts are used for ice removal. Like efflorescence, mineral salts are the cause for spalling – and pitting the thickness of a nickel is considered excessive and a restoration contractor will have to grind the tile to flatten the floor. Instead of the salts depositing on the surface (efflorescence) they deposit below the surface of the stone, causing pressure within the stone, causing stone spalls, flakes or pits. Unfortunately once a stone begins to spall it is almost impossible to repair. It is recommended that the stone be replaced.

There are several reasons why a stone will turn yellow. Embedded dirt and grime can give the stone a yellow, dingy look; waxes and other coatings can yellow with age; certain stones will naturally yellow with age as a result of oxidation of the iron within the stone. This is especially problematic with white marbles. If the yellowing is caused by dirt or wax build up, have the stone cleaned with an alkaline cleaner or wax stripper. This may be a job best left to professionals. If the yellowing is the result of aged stone or iron oxidation, it is not coming out.

Lippage is the term given to tiles that are set unevenly. In other words, the edge of one tile is higher than the next and it is the result of poor installation. If the lippage is higher than the thickness of a nickel, it is considered excessive and a restoration contractor can grind the tile to flatten the floor.

Cracks in the stone can be caused by settling, poor installation, inadequate underlying support or excessive vibration. Chips can result from a bad installation or when a heavy object falls on a vulnerable corner. Repairs can be done by a professional stone restoration contractor by filling with a color-matched polyester or epoxy.

Stun marks appear as white marks on the surface of the stone and are common in certain types of marble. These stuns are the result of tiny explosions inside the crystal of the stone. Pin point pressures placed on the marble cause these marks. Women’s high heels or blunt pointed instruments are common reasons for stun marks. Stun marks can be difficult to remove. Grinding and/or honing can reduce the number of stuns, but some travel through the entire thickness of the stone.

Water rings and spots are very common on marble and other natural stone surfaces. They are either areas that have become etched or are created from hard water minerals suck as calcium and magnesium that are left behind when water evaporates. To remove either type of these spots, use a marble polishing compound. Moderate to severe etching or larger damaged areas will require professional honing by a stone restoration contractor.

Hiring a Stone or Tile Pro

General Tips for Hiring a Contractor

When hiring any contractor, review them. Check at least 2 or 3 of their references, verify their insurance, see what professional organizations they are affiliated with and confirm they are a member in good standing. Don’t hesitate to trust your gut feeling – are you comfortable with the contractor? This is much more important than you might think.

Note: According to Consumer Reports, the biggest mistake consumers make is “being seduced by the price alone.” Would you hire the cheapest surgeon in town to operate on you or a member of your family? There is a saying, “Some of the most expensive work you will ever pay for is cheap work.” Consider that your home is your biggest investment, and you should always think long-term. Consider the consequences that saving a few dollars now will have over 3, 5 or 10 years of loving there. Your most important tool in evaluating the cost of a project is the value of what you are getting for your money. Low prices are usually a trade-off for cutting corners in materials, workmanship, warranty or adequate insurances. Remember that most average jobs can look good when completed. The true test is how they hold up over the next 10 years or more. Did the contractor use the proper methods and materials to give you a professional quality result? These differences are usually between a lower and a higher cost estimate.

Fabricators

Selecting Stone

Proper care and maintenance of stone starts with proper selection. It is essential that when you are contemplating a new stone installation that you carefully select your fabricator. A good fabricator will be qualified to help you make a selection that is appropriate for the environment that it will be in and the final result will be one you will be pleased with and endure beautifully. With that in mind, below are some rules of thumb.

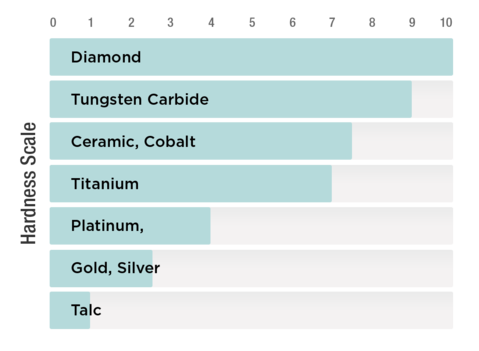

Calcite based stones – marbles, travertines, limestone, etc., will etch when acid comes in contact with it, so special care will have to be taken if using these stones in kitchens or other places where the likelihood is high that acidic liquids could be spilled on it. New topical treatments are available through specially certified applicators that provide an etch-resistant protective barrier. Marbles and other calcite-based stones are relatively soft stones as well, so this should also be considered (See MOHS scale diagram on below.)

Granite is an excellent choice for kitchen counter tops since it is not vulnerable to acids and is very hard (7 on the MOHS scale), so it doesn’t scratch easily. (Refer to the Lemon Juice and Oil Test for making your final selection.)

Soapstone is a very soft stone made of a variety of impure talc. (Talc is a 1 on the MOHS scale.) It is a very dense mineral that develops a warm patina as it wears and is often stain resistant.

Sandstone is a porous, durable sedimentary rock composed of cemented sand-sized grains, predominantly quartz. It is categorized by the most popular bonding agents such as silica, calcium, clay, and iron oxide. Sandstone is commonly used for flooring, counter tops, and vertical surfaces in both interior and exterior environments.

Quartzite is a common mineral (silicon dioxide, SIO2) and is usually colorless or white, although it may be colored by impurities. It has vitreous luster, conchoidal fracture, and is a 7 on the MOHS scale. There are several varities of quartz, including rock crystal, amethyst, chalcedony, and agate. It is commonly used for counter tops, flooring, showers, and vertical surfaces.

MOHS Scale

In 1812 the Mohs scale of mineral hardness was devised by the German mineralogist Frederich Mohs (1773-1839), who selected the ten minerals because they were common or readily available. The scale is not a linear scale, but somewhat arbitrary. An item with a higher MOHS value can scratch an item with a lower MOHS value. A lower-rated item cannot scratch a higher-rated one.

Kitchen counter tops with a 7+ are considered excellent, a 6 is good, a 5 is poor (because knives can scratch) and a 4 or below is inadvisable. When sediment and grit are harder than then surface, they will scratch and harm the stone.

A Note on Resining

Resining is a procedure that was introduced to the stone world by the Italians not too long ago to improve on the natural characteristics of certain stones, namely certain “granites” that are either too porous, or inherently prone to having a high percentage of natural flaws, such as fissures, pitting, etc.

The“resigning”of a slab is not done by the factories that process blocks into slabs. It is rather done by separate high-tech facilities where the slabs are delivered as they come out from the gang-saw, and before on of their two sides is further processed by grinding, honing and polishing. The slabs are enclosed in a vacuum-filled chamber, and a flowing resin is applied onto it. The vacuum environment helps the resin being deeply absorbed into the stone. After proper curing time, the slabs are sent back to the original processing plants, where they will be calibrated, ground, honed and polished. The resin will be totally eliminated from the polished surface of the slab and it will be exposed only as a filler of the possible natural fissure and pits of the stone and that would be otherwise unfilled and more or less obvious.

Is there anything wrong about such a procedure? Not really. There is indeed a lack of data about the long term effect (if any) of the resin inside the stone, but these are solid reasons to believe that nothing bad will come from it. Resin has been used in the stone industry for a few generations already. Once cured, the resin is chemically inert (thus totally safe) and will not react with most chemicals.

There are, however, a few things to be taken into consideration:

- 1. Sometimes the “resining” process is used to “upgrade” slabs. Translation: by resigning the low-grade slabs they will become “good,” If the resigning is done to eliminate the absorbency of the stone or to fill the natural pits, that is okay, but if it is done to eliminate the absorbency of the stone or to fill the natural pits, that is okay, but if it is done to mask some bad slab… well, you fill in the blanks. This is just another reason why the reputation of your fabricator is paramount. A reputable fabricator will never knowingly buy “doctored” slabs!

- While you could put a hot pot or pan right out of the stove onto “granite”, you could NOT do that if the slab had been resined. Irreparable damages to the resin may occur from the heat of the pot or pan reacting with the resin.

Certain resins may turn out to be photosensitive and its color altered over time if exposed to UV rays. Resined slabs are NOT recommended for outdoor kitchens and where they will be in direct sunlight.

All in all, “resining” is good (with the limitations listed above). Even “granites” that wouldn’t normally make the list of preferred stones would become more than acceptable if “resined.” The resin will be totally eliminated from the polished surface of the slab and it will be exposed only as a filler of the possible natural fissure and pits of the stone that would be otherwise unfilled and more or less obvious.

The Lemon Juice and Oil Test – A great test for selecting granite for your kitchen counter tops

It’s time now to select the stone for your kitchen counter tops. What do you look for?

Two things: Absorbency and acid sensitivity. You do NOT want a “granite” too absorbent, and you do NOT want a “granite” that is mixed with calcite (the main components of marble and limestone.) Line samples of any stone you are considering on a table or countertop, dust them thoroughly then pour a few drops of lemon juice and cooking oil on each one of them.

If you notice the stain immediately turns dark where the juice and the oil were applied to the stone, the stone is very absorbent and will not be ideal for a kitchen area.

If you notice that the juice and the oil take a little time to get absorbed (a half a minute or better), then you have a stone whose absorbency can be effectively controlled with a good quality impregnator. If you notice that some samples will not absorb anything within, half an hour or longer, then you may have a winner. That stone may not even need to be sealed. Now, how to eliminate the word ‘may’ from the equation? The answer resides in another question:

Why use lemon juice instead of, say, plain water? Because, as mentioned above, you’re not just looking to determine the absorbency of the stones you’re considering, but you also want to determine that your samples are 100% silicate rocks, opposed to some stones – still traded as granite – that are mixed with various percentages of calcite. If there’s even a little calcite in the stone, it will react to the high acidity of the lemon juice (citric acid). When you wipe your samples dry, you will notice a dull spot of the same shape of the lemon drops. If this is the case, this stone would not be a good candidate for a kitchen area. If instead it’s still nice and shiny where the drops were, then you eliminated the ‘may’ factor and have a stone that is acid resistant and has a low absorbency rate.

Stone Restoration Contractors

What Is Involved?

Restoration of marble, granite, limestone, travertine or other natural stone involves the removal of scratches and/or other damage from the surface of the stone. The optimal method is mechanical abrasion known as diamond grinding. Diamond grinding gives better clarity and reflectivity than other methods that can be used, such as the use of sanding screens, honing powders or crystallization. A stone floor that has been restored with diamonds will also retain its look longer than it will with the use of these other methods. While the use of diamonds may cost you more in the beginning, having your floors redone every 4-6 years compared to every 1-2 years (as with other methods) will cost you less in the long run.

Natural stone reflects light and therefore does not need a topical coating or wax to achieve this desired finish. It only needs a series of diamond grits used in the proper order by a craftsman who is experienced in their use. This is followed by a careful polishing technique that can only be mastered through experience. A restoration professional will also take care to protect the surrounding surfaces from damage. The diamond technique involves large amounts of water and this could be damaging to wood and carpet if measures are not properly taken to ensure the use of water was kept to a minimum and protection against splatter is used.

Choosing a Stone Restoration Contractor

Over a period of time all marble will be abraded, etched, and/or scratched depending on its use. Major restorations usually are best left to the stone restoration contractor. A contractor will evaluate the stone, the cause of the damage, and provide a concise plan to reach specific goals.

Do not compare bids on cost alone. You must have confidence that the restoration contractor understands the stone, has qualified employees, proper equipment and the experience to meet expectations. Determine in detail how the contractor will proceed and plan for the disruption such work involves. The contractor should recommend a maintenance program to assure longevity of the finished work.

Did You Know?

Cracks and chips in both marble and granite can be filled to look very natural.

Services a Stone Restoration Contractor Can Provide:

Grinding will remove deep scratches and lippage (uneven tile edges). This process is done by special floor machines with diamond abrasive pads and water that creates no dust.

Very visible seams in counter tops can be filled and mechanically polished to virtually disappear.

Honing will remove minor scratches and wear from everyday foot traffic. This process is also done by machine with diamond abrasive pads and water that creates no dust.

Gives marble or natural stone the sheen you want, enhances the veining in marble and protects the marble or stone from everyday traffics and spills. The same compounds that are used in the fabricating process are utilized.

A stone’s finish can be changed. For example, a honed finish can be changed to a polished finish and vice versa. Special brushes and techniques allow for additional decorative finishes.

Removes dirt, stains, bacteria, and also removes waxes and polymers that have become embedded. Cleaning alone will not change the physical appearance of the stone (removes etch marks and scratches).

To inhibit staining, an impregnating sealer is applied. Some more absorbent stones may require multiple applications.

The use of penetrating sealers/impregnators formulated to enhance or enrich the color of your stone.

Cracks and chips in both marble and granite can be filled.

Both limestone and travertine imperfections are filled at the factory. Unsightly blemishes that occur when factory fill fails or new ones develop can be filled.

Maintenance Services

Tile & Grout Cleaning Contractors

Sealing Grout – Clear or Color Sealing

Grout is porous and will absorb liquids, which can permanently discolor grout and create a haven for bacteria growth. Sealing your grout provides a protective barrier that not only protects it from stains, it makes routine cleaning and maintenance easier. Grout can be sealed with a clear sealer or it can be “Color Sealed.”

Having your grout sealed makes it less porous and provides some degree or protection, assuming a good quality sealer is used and is applied correctly. In this case, spills and stains will be less likely to permanently stain the grout. A common misconception that consumers have is that clear sealers are bulletproof. Although this is not the case, clear sealers will make daily maintenance easier, future restorations more effective and will allow a little time to catch a spill before the grout is penetrated.

Color sealing makes the grout completely waterproof. If a high-quality color seal product is used and is applied correctly the grout will look natural, not painted, and provide the highest level or protection available. When a floor has been color sealed you can spill block coffee on white grout and let it completely dry – the seal is so effective that it can be wiped off of the grout with mild cleaner, without leaving a trace or any stain.

Color sealing also has the added advantage that it allows you to completely change the color of your grout whether it is just for a new look or to cover up stained or discolored grout.

Tile Installers

Tile Flooring and Walls

- Cracked tiles

- Uneven grout lines

- Loose tile

- Hollow tile, which can result in cracks and tiles popping out

- The use of the wrong grout or setting material may result in failure

- Lippage – one tile higher or lower than the adjacent tile

Counter Tops

- Unlevel top resulting in one section higher than another

- Cracked tops

- Use of the wrong caulking can result in staining or water getting inside

- Misalignment of edges

- Tops that rock due to improper shimming

- Staining

Tips For Hiring an Installer

- While you may want to shop around for your tiles or stone, you may want to let the installer do that for you.

- Once you have your prospective installer candidates, schedule an appointment for an estimate. Almost all contractors will offer a free estimate. Be sure you are there for the scheduled time. It can be very frustrating for a contractor to arrive for an estimate only to find that no one is home. On the other hand, if the contractor doesn’t show for the scheduled appointment without calling first, he obviously does not deserve your project.

- Once the installer arrives, tell him what your concerns are and what you want. After all, you will be living with the floor or other installation every day. The installer is seeing it for the first time. Give him as much information as possible.

- Once the contractor has decided what is needed, ask him to explain the procedure he intends to use. Ask him if there are other options. A competent installer should be more than happy to answer any question you may have.

- Negotiating price. Some contractors will negotiate, while others will stick to their guns. However, if you mention that you are getting two additional estimates, he may sharpen his pencil knowing he is competing with others. One word of caution: be sure you are comparing apples to apples.

- Is he part of any professional organizations? Verify this. Ask for references and check them. Many contractors in all fields have references and you will be surprised how rarely they are actually checked. Call at least three and ask them if the contractor did a good job. Were there any problems and did he correct them? Were his employees professional?

- Does the contractor carry insurance? Ask him for proof. Have him show you a certificate of insurance – or if the job is large enough – have his insurance company send you one. Be sure he carries both liability and workman’s compensation insurance. Any reputable company will carry these insurances.

- Once you choose your installer, schedule the job. Don’t be surprised if the installer is booked for several weeks. Be patient – a good installer may be busy and you will have to wait your turn.

- Ask the contractor how long it will take to complete the job. This is an important point since many contractors are doing several jobs at once. Make sure the time schedule is in his contract. Be realistic – there are several problems that can occur that will delay the work. Even the best contractors can make mistakes. The difference between the good contractor and the bad is his willingness to correct those mistakes.